Not long after accepting a teaching position at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1964, Samia Halaby decided to abandon the painterly abstraction that she had developed while receiving her artistic training from universities in the Midwest. In search of a new start, she came across a fifteenth-century painting by Flemish master Petrus Christus in the collection of the Nelson Atkins Museum, an unassuming work that would nonetheless change the direction of her art. Virgin and Child in a Domestic Interior (1460-67) displays the fastidious realism of the Northern Renaissance, which catapulted religious iconography from the naïveté of medieval art while incorporating the details of lived spaces. In the composition a small orange resting on a windowsill near the holy mother and child is cast in shadow on one side and bathed in light on the other. Closely examining this compositional accent, Halaby began to devise a needed formal challenge.

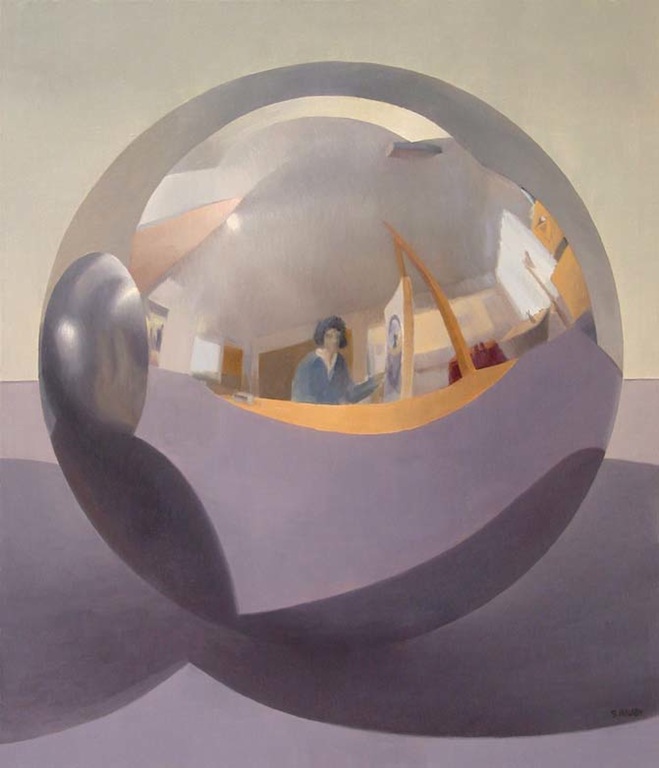

After several years of painting in total abstraction, she returned to figuration in order to examine how one understands the presence of edges when three-dimensional objects are rendered on a two-dimensional surface. In doing so, the artist was interested in how volume, space, and dimension could be rendered in the absence of illusionist perspective, edges, and shading, the key components of figurative painting. She began by building geometric models, or “still lifes,” which she then placed under various lights and in different locations of her studio. Over the course of several paintings, these objects (spheres, cylinders, cones, and squares) were isolated by the artist then visually sliced opened, reshaped, and repositioned. Through visual conjugation, she eventually arrived at a different approach to abstraction.

In such canvases as Largest Blue Green (1963), Halaby’s initial approach reflects American trends of the time, as the influence of Abstract Expressionism and other post-war schools of non-objective art are evident. Bold color fields vertically divide the picture plane, creating depth through contrasting bands, an experiment in tonal relationships derived from the groundbreaking theories of Josef Albers. Although the works of the Geometric Still Life series (1966-1970) demonstrate the artist’s ongoing explorations of color relativity and her previous objective of eliminating references to traditional perspective, they demonstrate a clear departure.

[Largest Blue Green (1963). Image copyright the artist.]

[Largest Blue Green (1963). Image copyright the artist.]

[Mirror Sphere (1968). Image copyright the artist.]

[Mirror Sphere (1968). Image copyright the artist.]

This sudden break would prove to be one of many for the Palestinian artist, who has spent the past five decades perfecting a materialist view of the world through abstraction. With each successive series of paintings, Halaby has worked through critical formal inquiries by utilizing observations from nature and modern life and reconsidering the seminal lessons of previous aesthetics, be they the continuum of volume and space of Islamic art or the breakthroughs in color and brushwork, and hence perception, of the Impressionists. Adhering to the directives of empirical analysis through which definitions are only established after thorough examination and many trials of experimentation, every period of her work has culminated in new findings. Practice before theory, as Albers advocated. Central to Halaby’s artistic practice are non-objective strategies that attempt to communicate the physical properties of matter: the interplays of light and color that create depth, volume, and movement; the numbers and rhythms constituting the growth of forms; and the continuous state of motion, or space and time, defining the fourth dimension. It is within this methodical treatment of form as it can relate to reality that the innovation of the artist’s extensive oeuvre can be found.

[Autumn Leaf Study (1975). Image copyright the artist.]

[Autumn Leaf Study (1975). Image copyright the artist.]

At the time of working through the fundamentals of figuration with the aim of arriving at a deeper understanding of abstraction, Halaby traveled to the Arab world and Turkey as part of a faculty development grant from the Kansas City Art Institute. Although she often revisited Islamic art and architecture as an artist in the United States, such exercises were exclusively through reproductions in books and invariably with a bittersweet sense of immediacy. The visual culture of her birthplace, as experienced through its historic architecture and the geometric abstraction of traditional crafts and design, had left a lasting impression on the artist. Returning to Palestine for the first time since 1948, she immediately gravitated towards the complex patterns and symmetry of the Dome of the Rock and studied the lower sixteenth-century marble inlays of its exterior, which consist of large geometric forms placed at the frontal edges of picture planes. Visiting Cairo, Damascus, Jerusalem, and Istanbul, she noticed how Islamic architecture merges volume and surface through its sophisticated ornamentation and structural designs in order to impact a given environment and facilitate social organization. Once completing this research intensive, she returned to her Missouri studio and immediately incorporated her observations into the Geometric Still Life series.

Halaby’s research trip to the Arab world and Turkey not only constituted a return to familiar territory, but also strengthened her commitment to the modernist ambition of creating a total work of art—one capable of surpassing the boundaries of visual culture, crossing over into the realm of sociotechnological advancement. Early on in her development, she was drawn to the linked endeavors of the Cubists and the Russian Futurists, Suprematists, and Constructivists and was exposed to the work of the Bauhaus while pursuing an undergraduate degree at the University of Cincinnati. In addition to serving as foundational guides for the evolution of abstraction in the twentieth century, such movements also reinforced the idea that as the introduction of new technology transforms the ways in which societies function, interact, and evolve, art must also reflect these changes by offering new ways of seeing. Aesthetics are thus essential to modern life, above all in the comprehension of its many components.

Form in relation to context is of utmost importance when considering the overhauling of art that occurred under the direction of Modernism. Cubism, for example, as it emerged with the works of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso between 1907 and 1910, attempted to reflect the breakthroughs in technology that were aiding mobility, communication, and the transfer of material culture. Figures and objects were deconstructed then reassembled into multidimensional, geometrically based, imagery in order to suggest volume in motion with references to time. Futurism, which immediately followed, furthered this pictorial breakdown by depicting the moments in which figures and objects are altered by force, as defined in physics, and thrust into space, creating pictures of the machine age. For the artists of the Russian avant-garde whose experiments accelerated the ripening of modern abstraction in the years leading up to the October Revolution, the organization of form, as explored through medium, composition, line, shape, and color, was the “objective of a new synthesis” directly related to sociopolitical developments. Constructivist Lyubov Popova, who began as a cubo-futurist painter, once observed that abstraction was not the “final form” but the “revolutionary condition of form.”[1] Popova’s description of non-objective art as maturing in tandem with political revolution serves as a reminder of the theoretical foresight that drove many of the twentieth century’s influential art movements as major power shifts occurred and societies changed. To speak of a “revolutionary condition” is to emphasize the potential of art to sharpen the eye and ignite the mind through its reliance on form as a conduit of communication. Without an evident progression of this fundamental quality, even the most discerning attempts to redirect visual culture will inevitably fail and quickly become irrelevant.

Although rarely discussed with regard to form, the evolution of Islamic art can also be understood within the rubric of visual culture pertaining to such historical developments. One of many illustrations of this point is its deliberate use of arabesques or geometric patterns across a given surface space, as abstract pictures containing the illusion of spatial depth and dimension are created. This pre-modern abstraction was partially adapted from Byzantine visual culture of the Eastern Mediterranean with the foundational aniconism of Islam. In Byzantine mosaics, which often depict religious figures or scenes of everyday life, mainly views of cities or pastoral landscapes, subject matter is accentuated with simple patterns. These secondary details were given new meaning and gradually expanded alongside developments in mathematics and the natural sciences in order to better serve the socioreligious contexts that were shaped by the spread of Islam. Through symmetry that balloons out from the center, minor sections are repeated and joined in a larger whole. As these designs reach a perceivable frame, for example the perimeter of a dome or the border of a manuscript, they infer infinite growth from a single source, evincing the vastness of the natural world with reference to the sublime. The distinguishing movement and continuous sense of time of Islamic art is thus derived from the overlay of forms that define space but eventually appear to defy its outermost edge.

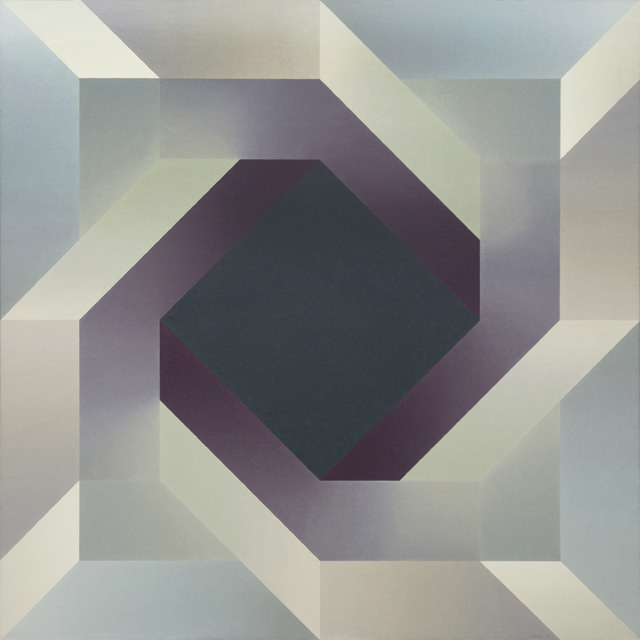

[Third Spiral with Black Center (1970). Image copyright the artist.]

[Third Spiral with Black Center (1970). Image copyright the artist.]

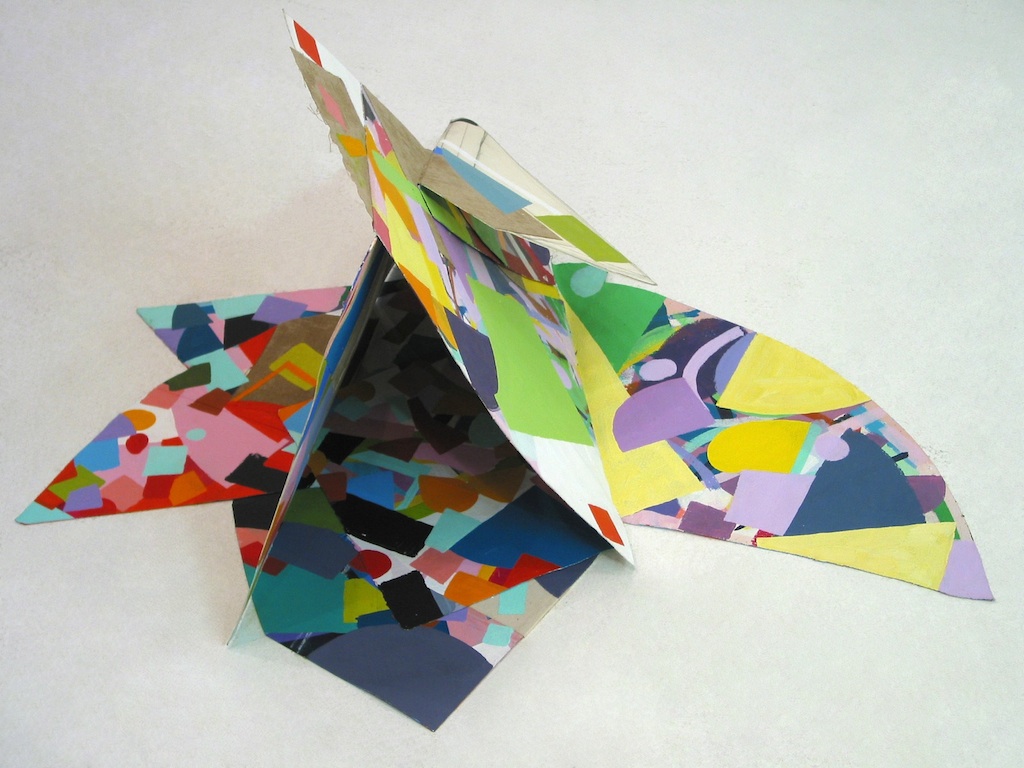

In Third Spiral with Black Center (1970), the final painting of the Geometric Still Life series, Halaby turned to Islamic art and modern abstract painting when attempting to abandon the properties of figuration that depend on illusionist perspective. At the center of a spiral growing from an octogram is a smaller black square. Since this area functions as the focal point of the painting, an immediate connection to the immeasurable space and volume of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915) can be made. Halaby’s use of color to intensify this volume—especially in the gradation of tones appearing in the rings of the spiral and the two larger squares forming an inner/outer area of the composition—recalls the Homage to the Square series through which Joseph Albers applied his color theories over the course of twenty-five years and through more than one thousand works. Most importantly, however, is the artist’s use of geometric abstraction in the formal tradition of Islamic art, which creates the sense of infinite growth, space, depth, and movement exclusively through line and color, a contrast alluding to an instance of darkness illuminated by light. Third Spiral with Black Center marks the end of the artist’s formative period. Having set aside the tangible influence of her academic training, she returned to her earliest exposure to abstraction in Palestine prior to 1948 while establishing a theoretical base that allowed her to conceive of abstract painting as an engagement with reality. Third Spiral with Black Center would eventually lead to radical experiments in how to move beyond the confines of the picture plane, including Kinetic paintings created through a computer program of her own design and hanging papier-mâché sculptures.

[Worldwide Intifada (1989). Image copyright the artist.]

[Worldwide Intifada (1989). Image copyright the artist.]

[Pyramid (2011). Image copyright the artist.]

[Pyramid (2011). Image copyright the artist.]

Halaby often contends that viewers are not required to know what inspired individual works since formal attributes allow the eye to recognize what is familiar to the mind as registered through experience. In Forms Conceived as Language, Asger Jorn outlines “materialist realism” as seeking “the forms of reality that are ‘common to the senses of all men.’” This description is useful when attempting to understand how artists such as Halaby have furthered abstraction. Materialist philosophy upholds that sensations are “images” of phenomena resulting from interactions with matter. From such images of the external world, we deduce principles, theories, and consciousness. Therefore, as the artist recreates the physical properties of things found in nature or in built environments, focusing on intensity, luster, momentum, opacity, radiance, and so forth, she utilizes form to trigger experiential sensation in the process of recognition.

*Samia Halaby: Five Decades of Painting and Innovation is on view until 30 April at Ayyam Gallery (Al Quoz), Dubai.

[1] Rodchenko and Popova: Defining Constructivism (London: Tate Publishing, 2004).